The Big Debate:

A Case to Stop the Arundel Bypass

The case against Grey, and similarly against any long new dual carriageway through the countryside and villages, was and is many-faceted.

From time to time we shared communications on each of these aspects as papers or blogs. These may be found as links expanding the summary points below.

In summary, these are:

-

The transport science case

-

The climate emergency case

-

The economic case

-

The environmental case

-

The heritage case

-

The moral case

-

The political case

-

The practical case

The transport science case

Government, the Department for Transport and Highways England are not following the science.

They are failing to act on empirical science, ie evidence collected about whether practices work or don’t. Highways Agency studies a decade ago in 2009, as the Campaign for Better Transport reports, already showed Bypasses typically don’t work. They don't reduce traffic. Instead, they encourage more people to drive and often just move the problem a few miles away.

National and international traffic experts have stated the case for the cancellation of the Arundel Bypass.

From the Victoria Transport Policy Institute's Executive Director Todd Litmann, on 'generated' or 'induced' traffic:

Traffic congestion tends to maintain equilibrium; traffic volumes increase to the point that congestion delays discourage additional peak-period trips. If road capacity increases, peak-period trips also increase until congestion again limits further traffic growth. The additional travel is called “generated traffic.” Generated traffic consists of diverted traffic (trips shifted in time, route and destination), and induced vehicle travel (shifts from other modes, longer trips and new vehicle trips). Research indicates that generated traffic often fills a significant portion of capacity added to congested urban road.

Generated traffic has three implications for transport planning. First, it reduces the congestion reduction benefits of road capacity expansion. Second, it increases many external costs. Third, it provides relatively small user benefits because it consists of vehicle travel that consumers are most willing to forego when their costs increase. It is important to account for these factors in analysis. This paper defines types of generated traffic, discusses generated traffic impacts, recommends ways to incorporate generated traffic into evaluation, and describes alternatives to roadway capacity expansion.

The above is the Abstract of a longer July 2020 article by Todd Litman, Generated Traffic and Induced Travel: Implications for Transport Planning. A version of this paper was published in the ITE Journal, Vol. 71, No. 4, Institute of Transportation Engineers (www.ite.org), April 2001, pp. 38-47.

In October 2020, Todd Litmann issued the following statement: "The A27 Arundel Bypass is an example of a costly project that contradicts virtually all other planning goals, including goals to encourage resource-efficient travel, preserve greenspace, and improve mobility options for non-drivers. I therefore recommend that it be canceled, and the resources be invested instead in more efficient and equitable travel options." See further in Victoria Transport Policy Institute: "A27 Arundel Bypass - Reasons to Cancel", 2.11.2020

From Professor John Whitelegg, Visiting Professor of Sustainable Transport at Liverpool John Moores University, Oct 2020:

Sir David Attenborough has said: “It may sound frightening, but the scientific evidence is that if we have not taken dramatic action within the next decade, we could face irreversible damage to the natural world and the collapse of our societies.” Taking ‘dramatic action’ means no more new road building or bypasses and serious attention to the rich menu of non-road-building alternatives that are zero carbon, lower cost than roads and do not damage nature, countryside or biodiversity.

Those who promote schemes like the A27 Arundel bypass are promoting a failed intervention that will not achieve its objectives, a costly and highly wasteful use of public money and an option that will make the climate emergency worse. The A27 Arundel Bypass must be cancelled immediately and the funding retained in that geographical area for world-best walking, cycling, public transport, car-free streets and towns, shared vehicles and sustainable freight transport.

See further Professor John Whitelegg: "The Arundel Bypass must be cancelled. Professor Whitelegg also outlines what a more effective approach than just banning petrol and diesel vehicles' sale might look like in this 17.11.2020 piece written for the Foundation for Integrated Transport.

From CPRE's report written by TfQL, 'End of the Road':

From Articles collection in World Transport Policy & Practice, Volume 26.3, August 2020

This issue of the journal has a collection of commissioned articles on the shape of transport and mobility after Covid-19. The 6 authors were asked to produce ‘think pieces’ looking ahead to what the transport world could and should look like after the extra-ordinary coronavirus experience has subsided. These “think pieces” have also been submitted to the UK Department of Transport to inform its work on ‘Decarbonising Transport’ and ‘The Future of Transport Regulatory Review’. All the authors have a wealth of experience to bring to bear on the future of transport and mobility and the degree to which the virus crisis has shifted the prevailing deviant paradigm.

So why does government appear to be acting as if going over to electric cars means they can build major new roads indefinitely?

From House of Commons Science and Technology Committee 20.7.19 Report: "Clean Growth: Technologies for meeting the UK’s emissions reduction targets", para 131: Para 131 is quoted in the introduction to this section.

One objective which we (and the Committee) feel is critical, is highlighted: a reduction in ‘the number of vehicles required'.From a paper Decarbonising transport: Accelerating the uptake of electric vehicles, published by Oxford University's Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions (CREDS),

Although electrification is an essential part of the long-term transition to zero emissions transport, it is not a panacea. Electric vehicles (EVs) today are lower emissions per mile driven than a petrol or diesel equivalent when the emissions from the fuel or electricity are counted (well to wheel).

However, across the whole lifecycle, from construction to decommissioning, an EV today emits broadly the same level of CO2 as an Internal Combustion Engine (ICE). As production processes shift to using renewable energy the whole life CO2 benefits of EVs will grow, but today there is no such thing as a ‘zero emissions vehicle’.

The realities of price, vehicle availability and consumer choices also influence the rate at which EVs can be brought into the fleet. Even with an accelerated phase-out date of 2032 or 2035 for ICEs, the emissions from the car fleet will still be well above local authorities’ necessary carbon reduction trajectories.

There is no decarbonisation strategy which can rely solely on changing the vehicles that people drive, so the uptake of EVs and how this is managed needs to be treated carefully, alongside efforts to encourage mode shift away from the car and to reduce the overall demand for travel.

An extended FoE paper brings together data from transport and climate science studies which show that even a very rapid switch to electric cars will not reduce greenhouse gas emissions enough, but that in addition, traffic levels need to be reduced by at least 20%. By contrast Highways England, in seeking to justify approaching half a billion pounds investment in the Arundel Bypass Grey Route, are choosing to predict and provide a wholly unsustainable traffic increase.

A 2018 European detailed study showed an average electric vehicle's emissions are 75% of those of an average petrol car (across lifetime of vehicle) across the EU - varying according to power supply mix. Over this hangs the carbon cost of continuing road expansion, and extra fossil fuelled power from increased demand on power network. Both road-building and car numbers must reduce to address the climate emergency.

Consider two further questions which are essential to the question of how far conversion to electric vehicles is from being a sufficient transport science solution.

-

Q1 How much renewably sourced electricity will there be during the supposed decarbonisation trajectory?

Although the growth of renewable electricity has been strong, the rate of growth has been declining fairly rapidly. The existing trend would not produce carbon-free electricity by 2050 for the whole economy, even assuming transport policy does not induce more traffic than at present. The national consumption of fossil fuel energy that remains to be decarbonised is 113Mtonne, excluding our imports of embodied carbon and our international aviation and marine bunkering fossil fuel consumption.

-

Q2 How much of that total electricity ought to be directed towards transport?

The Metz effect of road construction has shown that journey lengths expand to fill the time available – we drive further for the same level of economic activity – we do this because we do not perceive or pay for the externalities. Hence much of transport activity is neither necessary nor efficient and should be treated as discretionary activity. Much less discretionary forms of energy demand, which therefore have a better claim on the available renewable electricity, include the heating and lighting of houses, hospitals, schools and places of work sufficiently for habitation, as well as the energy for basic industrial and agricultural production.

On 1.1.21, Professor John Whitelegg wrote an Open Letter to Grant Schapps, which can be read here.

The climate emergency case

In terms of carbon emissions, transport is the worst-performing sector of the UK economy. Whereas emissions in all other sectors have fallen, emissions from transport are still going up. The Department for Transport has stated that the forecast rate of carbon reduction from transport is much slower than is needed.

The climate change imperative to reduce traffic

Click here to read about, and for a link to, the Climate Change Committee (CCC)'s 2022 Progress Report. This criticised the Government's road-building plans for increasing demand and emissions. It stated that they should not be encouraging unconstrained traffic growth and needed to be compatible with net-zero. Could we finally be turning the corner on road building in England? There is hope, but the Government's history on this means it's far from certain there will be the essential follow-through.

On 9.12.2020 the the Climate Change Committee (CCC) published their 6th Carbon Budget. On p. 97, on surface transport, it says:

‘Key elements of the ‘balanced pathway’ are:

Reduction in car travel. We assume that approx. 9% of car miles can be reduced (e.g. through increased home working) or shifted to lower-carbon modes (such as walking, cycling and public transport) by 2035, increasing to 17% by 2050.

The opportunities presented to lock-in positive behaviours seen during the Covid-19 pandemic and societal and technological changes to reduce demand (e.g. shared mobility and focus on broadband rather than roadbuilding) are key enablers.’

This projected volume reduction fatally undermines the already highly questionable business case for the Arundel Grey Route, in stark contrast to the view expressed by Highways England's A27 programme director Jason Hones, that HE wish to regard the changes such as increased home-working seen in the Covid pandemic as "a blip".

The analysis in the preceding transport science section, on how far switching to electric vehicles can (and cannot) go towards solving the problem of transport's contribution to the climate emergency, is equally pertinent here.

The House of Commons Science & Technology Select Committee, in a report published in July 2019, Clean Growth: Technologies for meeting the UK’s emissions reduction targets, concluded (para 131):

The transport sector is now the largest-emitting sector of the UK economy. ... There are significant emissions associated with the manufacture of vehicles. In the long-term, widespread personal vehicle ownership does not appear to be compatible with significant decarbonisation. The Government should not aim to achieve emissions reductions simply by replacing existing vehicles with lower-emissions versions.

Alongside the Government’s existing targets and policies, it must develop a strategy to stimulate a low-emissions transport system, with the metrics and targets to match. This should aim to reduce the number of vehicles required, for example by: promoting and improving public transport; reducing its cost relative to private transport; encouraging vehicle usership in place of ownership; and encouraging and supporting increased levels of walking and cycling.

The government is following the science to the extent of bringing forward the banning of conventional higher-emissions vehicles. But it is not, yet, following its own Science & Technology Select Committee's recommendations in permitting Highways England to plan and invest in increased numbers of vehicles, rather than managing for reduction and investing in alternative systems.

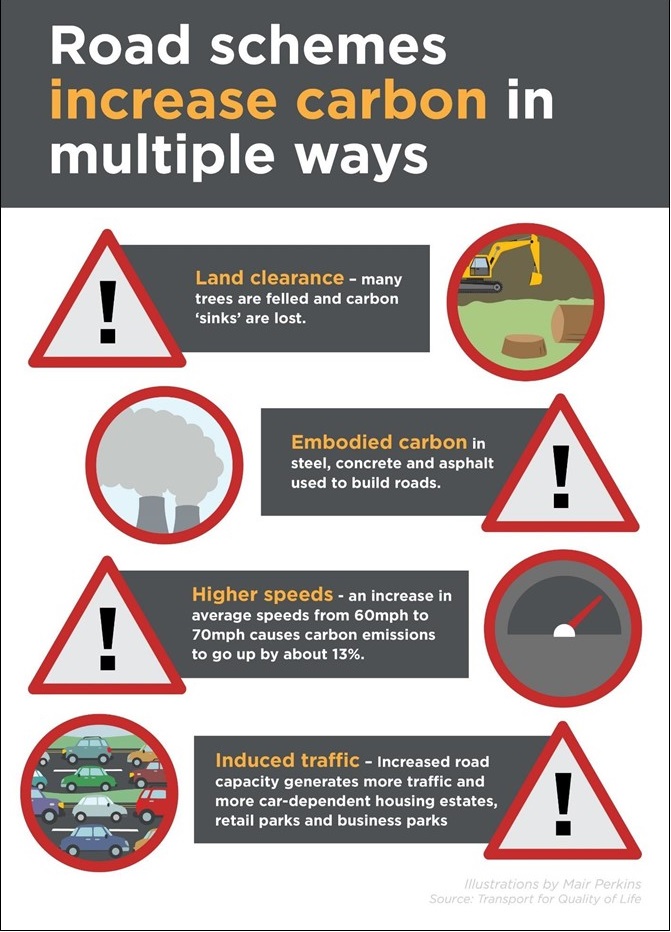

From Lynn Sloman's “The carbon impact of the national roads programme,” Sloman and Hopkinson, July 2020.

(Thanks to Mair Perkins for the illustration, licensed for reuse under Creative Commons Licence)

-In terms of carbon emissions, transport is the worst-performing sector of the economy. Whereas emissions in all other sectors have fallen, emissions from transport are still going up.-The Department for Transport is developing a decarbonisation plan for the transport sector, and has stated that the forecast rate of carbon reduction from transport is much slower than is needed.

-The Climate Change Act 2008 now commits the UK to reduce net carbon emissions to zero by 2050, and to five-yearly carbon budgets between now and then. The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) has already shown that transport is not even on track to comply with existing carbon budgets (set when the target was to reduce emissions by 80% by 2050), let alone net-zero ones.

-However, in terms of impact on the climate, what matters is not so much the end date, as the total amount of CO2 that is emitted between now and then. Under the Paris Climate Agreement, the UK is committed to restricting the increase in global average temperatures to well below 2°C and preferably below 1.5°C. For this, cutting carbon emissions over the next decade will be crucial. (p. 3).We believe that DfT should set a binding Paris-compliant carbon budget for all parts of the transport sector, including Highways England which is responsible for the SRN. By analogy with carbon budgets proposed for local authorities by the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change, we estimate that a fair, Paris-compliant budget for the SRN [Strategic Road Network] between now and 2032 is about 214 MtCO2. (p. 3)

RIS2 [the Government’s new roads programme] will make carbon emissions from the SRN go up, by about 20 MtCO2, during a period when we need to make them go down, by about 167 MtCO2. …This suggests that RIS2 is incompatible with our legal obligation to cut carbon emissions in line with the Paris Climate Agreement, the Climate Change Act budgets and the emerging principles for the Departement for Transport’s decarbonisation plan. We therefore believe that it should be cancelled. DfT has not published any assessment of the cumulative carbon impact of RIS2. (p. 4)

The COVID-19 pandemic has wrought enormous behaviour change, with both work and non-work journeys replaced by a variety of video conferencing solutions and greater use of local facilities. When rebuilding the economy, it is vital that investment supports behavioural shifts that will also help to achieve reductions in carbon emissions. Cancelling RIS2 would free up investment for this. (p. 5)

From Emeritus Professor of Transport Policy Phil Goodwin, Centre for Transport and Society, University of the West of England, Bristol, and University College London, on Highways England's failed carbon impact assessment approach:

Greg Marsden, Professor of Transport Governance at the Institute for Transport Studies at the University of Leeds and the Transport Decarbonisation Champion for Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) is clear about the urgent need to reduce transport carbon emissions. The solution he strongly recommends is to “Stop making the problem bigger”. National Highways and transport planners must stop making the problem bigger by building new roads. There should be an immediate moratorium on the construction of new roads. This would stop the increase in carbon emissions from transport. Otherwise, we will fail to reach net zero targets.

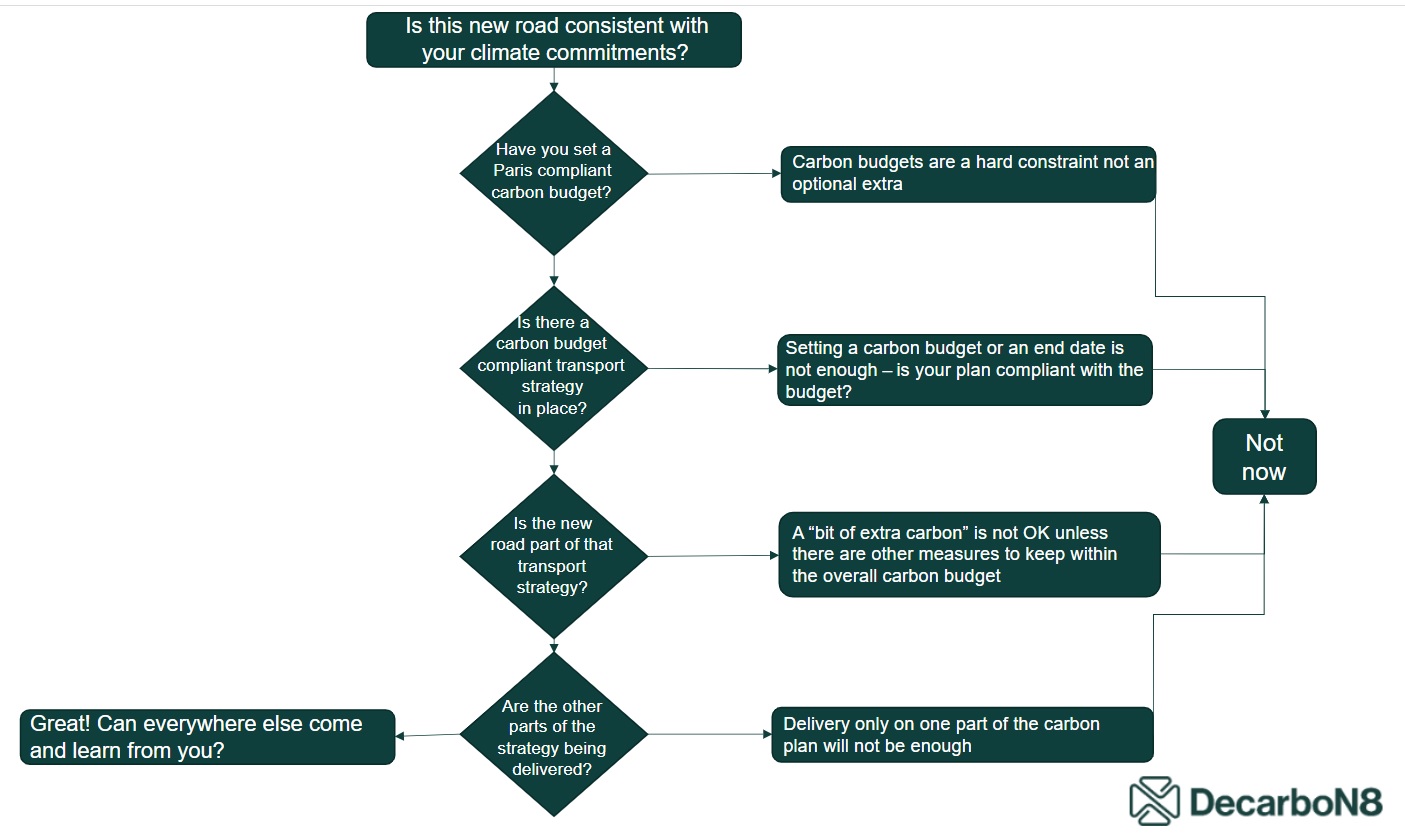

Electrification isn't enough to reduce carbon emissions fast enough to meet the net zero target by 2050. Transport planning must be for fewer cars and more shared cars. This means we don’t need more road capacity. The strategy for road infrastructure should be maintenance and adaptation, not new build. We should reallocate, not expand road space, ensuring high quality infrastructure is provided to enable walking, cycling and more micro mobility. Accommodating more motor vehicles and encouraging more car trips, which the proposed bypass will do, will make things worse. See: https://decarbon8.org.uk/is-this-new-road-ok/

Following are two excerpts from “Computer Says Road,” written by David Milner, a Create Streets Briefing Paper https://www.createstreets.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Computer-says-road-1.pdf

Page 2: We treat the results of transport prediction models as an uncontested fact, yet they are neither sophisticated enough to balance all the ways in which we travel around nor agile enough to adapt to changing technology and human behaviour. We must change how we use them so we can design the infrastructure we really need.

Page 8:

- A common assumption is that spending on more and wider roads will ease congestion. However, multiple studies have found that building new roads does not achieve this goal and is, instead, generating more journeys and more traffic. An American study found that there is an almost perfect one-to-one relationship between new roads and new traffic added. A study in Norway found similar results.

- When the M25 was widened from three to four lanes traffic increased at an almost perfect 33 per cent in one year.

- A UK study by Prof Phil Goodwin found that traffic increased by an average of 47 per cent above background growth following road expansion projects.

- In 2009 the National Audit Office stated that ‘previous experience shows that new road capacity rapidly fills, reducing the benefits of making more road available’.

- And in 2017 the DFT rejected a proposed road-widening scheme, asking that planners ‘work first to find alternatives to travel, or to move traffic to more sustainable modes’.

- In summary, widening roads creates entirely new journeys, as opposed to taking the load from other roads. They do not reduce the time you spend stuck in traffic and merely shift journeys from other types of transport or replace a Zoom call, by making it easier to drive.

-

The economic case

Promises of more big roads are often made to raise voter confidence in economic prospects, but they are not what we need to rebuild today's economy or that of the future.

The economy is changing already

PM Boris Johnson spoke in September 2020 of the need to steer a "build back greener recovery" post-Covid; and in July 2020 Transport Secretary Grant Schapps also spoke of "green recovery" and announced "a 'revolution' in sustainable, climate-friendly transport". But their Department of Transport and its wholly-owned road-building company Highways England are still intent on delivering the opposite.

All over the world people are waking up to the need to take positive steps to accommodate and facilitate a new economic reality. "We're recovering, but to a different economy," said Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell on 12.11.20 during a virtual panel discussion at the European Central Bank's Forum on Central Banking. The pandemic has accelerated existing trends in the economy and society, including the increasing use of technology, telework and automation, he said. This will have lasting effects on how people live and work - and travel. As the climate science insists it must, to secure any viable future economy.

In a 9.12.20 BBC News article 'Climate change: Low-carbon revolution "cheaper than thought"', Roger Harrabin reports the Climate Change Committee's top recommended condition for success as, "To reduce demand for activities that increase carbon emissions. This means curbing the projected growth in flying and leaving cars at home wherever possible." Traffic must reduce. Spending half a billion on a new 8km 4-lane A27 Arundel Bypass no longer makes any sense - if it ever did. Electric vehicles are lower-emissions than fossil fuel, but their climate and environmental impact is still substantial, and growth in vehicle journeys is unsustainable even if electric - see this article on electric cars for more information.

On 2 Feb 2021, UK Treasury's commissioned report by Professor Dasgupta, 'The Economics of Biodiversity: the Dasgupta Review", was published. PM Boris Johnson welcomed the report saying, “This year is critical in determining whether we can stop and reverse the concerning trend of fast-declining biodiversity. I welcome the review, which makes clear that protecting and enhancing nature needs more than good intentions – it requires concerted, coordinated action.” However, welcoming words have yet to be translated into action. "Continuing down our current path presents extreme risks and uncertainty for our economies” according to the review. And yet, this government is still contemplating, for example, spending nearly half a billion on an A27 Arundel Bypass road scheme that, to save just a few minutes' travel time, will create massive ecological severance impacts adding to local and migratory species extinction pressures, in an area whose biodiversity Natural England has described as 'extraordinary'. The Dasgupta review concludes: “To detach nature from economic reasoning is to imply that we consider ourselves to be external to nature. The fault is not in economics; it lies in the way we have chosen to practise it. Transformative change is possible – we and our descendants deserve nothing less.” New measures of success are needed to avoid catastrophic breakdown - and yet, the measures Highways England employ are continuing to promote a breakdown, whose impacts are not being factored in to economic decision-making.

Value for money

Spending up to half a billion on the Grey Route across Arundel is a poor value for money investment by any standard. The reasons why this is so are set out in the paper on this link:

Why the A27 Arundel Bypass Grey route is not good Value for Money

To summarize some key points:

Value for Money. The case supporting value for money is built by comparing forecasts of monetised benefits with forecasts of construction and other monetised costs; in this way a benefit to cost ratio (BCR) is produced. The BCR is overlain by a judgement to account for things that cannot be monetised, such as expected effects, risks and uncertainty so as to assess the net increase in overall public value. This outcome is labelled Value for Money. Highways England produces both the BCR and the value for money judgement, sometimes using its own unpublished guidance and otherwise using Department for Transport guidance. Both the costs and the benefits for the Grey option are open to question such that its BCR and thus its Value for Money are in serious doubt. Those who have been pressing Highways England for over a year on the issues involved have received no cogent responses, itself indicative of considerable problems. We now estimate that the BCR is very roughly one-third of the publicised figure, an outcome that would normally place it well outside the government guidelines for acceptance.

Costs. Grey starts off as the most expensive route option and the largest excluded cost issue we are aware of is the decision on the use of a viaduct in place of an embankment to cross the Arun floodplain. The additional cost could be in the region of £300 million, on top of Grey’s current upper cost estimate of £455 million. At the other end of the scale of currently unincluded costs is the compensation due in Walberton for the complete removal of the existing site access to an estate of 175 houses now under construction.

Benefits. There are several large benefits issues still outstanding after a year. One is the effect of the assumption in Highways England’s traffic model that both the Lyminster bypass and the 2017 Worthing Lancing scheme are already built. This assumption follows recent guidance by Highways England to itself, which overrides the fact that the Worthing Lancing scheme is not to be built. Other benefit issues outstanding are technical but clearly suggest that Highways England’s traffic model assumptions lead it significantly to overstate future traffic volumes for the Grey option; this is important because "benefits" are overwhelmingly dependent on these volumes.

Were the environmental and social costs to be monetized, the misspend scandal would be even more extreme.

Department for Transport VfM Indicator (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/percentage-of-dft-s-appraised-project-spending-that-is-assessed-as-good-or-very-good-value-for-money)

Department for Transport Guidelines (https://www.gov.uk/guidance/transport-analysis-guidance-tag.)

Department for Transport VfM Framework https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/918479/value-for-money-framework.pdf).

The environmental case

This case is conclusively if not exhaustively set out in the responses of the Defra agencies, Natural England and Historic England, to the 2019 consultation; and Natural England's damning response to the 2022 consultation. The whole area is 'extraordinary', according to Natural England. It has been extensively surveyed by Arun Countryside Trust and also by Highways England ecologists. A great diversity of habitats are found here, used by many diverse species in connected combination. There are an exceptional 14 species of bats, some in very large numbers, foraging and travelling across the Grey Route. The area has the largest regularly surveyed dormouse population surviving in the UK, water voles - you name it.

Extensive severance of the Arun Valley watermeadows, and of the woodlands from the wetlands to the west, together with direct impacts by the Grey Route would be environmentally disastrous and impossible to adequately mitigate. Serious environmental damage includes direct and indirect, short and long term ecological, heritage, hydrological, landscape and climate impacts.

The Myth of Mitigation

From the Arun Countryside Trust Response to the A27 Arundel Bypass Scheme Options 2019:

Within the Mid Arun Valley, the natural habitats and landscape as at present managed, support rich biodiversity, including thriving bird communities, a large and stable Dormouse population, thousands of breeding toads, key reptile sites, a nationally important bat assemblage and several important invertebrate communities These communities have persisted for millennia, despite a changing world.

Mitigation and compensation (that may be maintained for 25 years and monitored for fewer years) are unlikely to result in net biodiversity gains for such a rich and largely interdependent assemblage.

The current Scheme is being proposed against a backdrop of continual species decline in the face of yet another factor - climate change - resulting in a layer of unpredictability (i.e. ponds drying, cold snaps, localised flooding, lack of availability of prey source at critical times etc.)

The numerous impacts should be used as a way to navigate to the least damaging Option for Arundel and its rich assemblage of wildlife, which, evaluating the operational and residual effects is the Cyan or Beige Option.

[Note: the ACT quote above was commenting within the framework of the options offered; elsewhere ACT pointed out the Arundel Alternative, not offered by Highways England, is less damaging than Cyan or Beige.]

"Resilience and functionality of this extraordinary ecosystem" requires an online, not offline solution

From Natural England’s response to the 2019 Consultation:

We have advised Highways England that the impacts on wildlife and landscape are considerably greater with offline schemes. This is because offline schemes include both habitat loss and the permanent severance of remaining habitats affecting the resilience and functionality of this extraordinary ecosystem, and diminishing its ability to adapt to the effects of climate change. Furthermore our landscape advice remains that, the online schemes offer the potential for the least damaging scheme in terms of landscape character and visual amenity.

We have advised that in order to ensure a robust assessment of the impacts of severance the critical factor is to assess each option in an integrated way at a landscape scale. We have provided Highways England with a joint letter from Natural England, the South Downs National Park, Environment Agency and the Forestry commission presenting our united concerns, of which severance is an overarching theme. (page 1)

It is with concern therefore that we advise that the impact of severance has not yet been adequately assessed in the brochure or accompanying supporting evidence. Without a clear and balanced assessment which highlights this major impact, a judgement of the true scale of environmental impact presented by offline options cannot be made.

This letter highlights our considerable concerns regarding landscape and the impacts that the options have for biodiversity via loss and severance of habitats. We will reiterate our advice that this area is extraordinary, necessitating a bespoke approach to assessment across the suite of priority and irreplaceable habitats and the associated array of species that this nationally important environment contains. (page 2)

The South Downs National Park

From the South Downs National Park Authority response to the 2019 Consultation:

As presented, all the [6 Highways England] routes, including the route outside the SDNP (grey route), impact negatively on the SDNP and its setting. To varying degrees all would cause significant harm to the biodiversity, cultural heritage, access, recreation potential and landscape character of the SDNP

SDNPA urge Highways England to address, as a priority, the shared concerns raised in the Single Voice letter sent by the DEFRA family, which i) highlighted the issues of an embankment as compared with a viaduct – which conflict with HE assessments – ii) the issue of connectivity and also iii) the issue of environmental net gain.

-…the mainly on-line Cyan and Beige routes, though potentially the least damaging for most of the Special Qualities of the SDNP, would have very significant unmitigated/compensated impacts on Ancient Semi Natural Woodland, and the townscape. By contrast the Crimson, Magenta, Amber and Grey routes ... still have significant impacts on the SDNP special qualities and would have major impacts on its setting.

Flood risk and hydrological management are a big issue. The Grey route has been costed with an embankment forming a barrier across the Arun valley flood plain.

From the Environment Agency’s response to the 2019 Consultation

This report identifies Flood Risk (“we are still concerned that the impact the proposed options may have on tidal flood risk has not yet been properly considered.” page 2), Biodiversity (“major adverse risks to nature conservation from all six options presented,” page 4), Groundwater Protection (page 5-6), and Drainage (page 6).

…any option for the bypass should be considered in an integrated way at a landscape scale to ensure that the complex and interconnected ecosystem that is set within wider hydrological catchment are fully understood and reflected in design choices. (page 7)

The importance of small streams and water bodies. The Grey route would sever multiple chalkstream habitats.

Twenty scientists wrote on 1st Dec 2020, on behalf of the Freshwater Habitats Trust, to the Natural Capital Committee, urging the importance of protecting this under-recognized, high-ecological-value water body type: their letter can be read here. This was also commented upon for example in the BBC article "Small waters 'can help address biodiversity crisis'" and the Freshwater Habitats Trust newsletter gives further information.

The Binsted Rife and Tortington Rife are both complex chalkstream catchments with multiple small tributary streams ponds and marshes. These support many rare and threatened species, from water voles to the rich insect population which supports 14 species of bats in the area. The Grey Route would have a severe detrimental impact on the biodiversity of this 'extraordinary' (Nat. England) wetland network, both by direct impact, by severance, and by pollution.

Think globally, act locally

From Simon Rose, Arundel SCATE (linked to South Coast Alliance on Transport and the Environment), October 2020:

We know we have to tackle climate change, yet Highways England options would significantly increase carbon emissions. The UK Climate Assembly recommended we need to cut traffic to cut carbon emissions, and academic research also tells us we must cut traffic, even if we switch to electric vehicles in the most optimistic timescale. So why is Highways England planning for more traffic?

This area, described by Natural England as ‘extraordinary’, includes ancient hedgerows, rare wetland, old woodland and ancient trees which are important corridors for protected species such as dormice and rare bats. Further to the east, the road would carve up fields, marsh, river bank and reed beds, rich in birdlife, small mammals and butterflies. The riverbank where the road would cross, is a popular walk for Arundel people, dogs, birdwatchers and visitors. All potentially lost to acres of tarmac raised on a bank across the Arun Valley.

The UK Environmental Audit Committee's Biodiversity and Ecosystems Report, 30.6.21

As reported in BBC Science 30.6.21, the MPs' committee report "Biodiversity in the UK: Bloom or Bust?" concludes that the government’s underfunded green ambitions and “toothless” policies are failing to halt catastrophic loss of wildlife. According to the report, existing policies and targets are simply inadequate and not joined up across government. The report finds the biodiversity crisis is still not being treated with the urgency of the climate crisis. The UK is the most wildlife-depleted country out of the G7 nations and, despite pledges to improve the environment within a generation, properly funded policies are not in place to make this happen. More money is being spent destroying the environment than protecting it. Recommendations include creating a commission to track public expenditure that harms biodiversity, removing harmful subsidies and redirecting money into nature conservation. Philip Dunne, the chairman of the committee, said despite countless policies to improve the natural environment, they remain “grandiose statements lacking teeth and devoid of effective delivery mechanisms”. He said: “We have no doubt that the ambition is there, but a poorly mixed cocktail of ambitious targets, superficial strategies, funding cuts and lack of expertise is making any tangible progress incredibly challenging.”

The historic environment

From West Sussex County Council's response to the 2019 consultation:

"The noise, townscape and historic environment impacts of Option 5BV1 (Grey) have been underestimated because the environmental assessment has not taken account of impacts on the Avisford Grange development at Walberton or some impacts on the historic environment. The latter includes: (a) the severance of Binsted as a historical settlement into three parts, isolating its most ancient and historically important building, St Mary’s Church; and (b) severance of the view along the Binsted Rife valley by crossing this very visible feature of the local historical landscape in an open area.” (p294)

St Mary's Church is a Grade II* listed building. Alongside Grade I and world heritage sites, UK planning policy states that its setting should only be allowed to be impacted in "wholly exceptional" circumstances.

Direct impacts of the overbridge ramps on listed buildings Meadow Lodge and Morleys Croft are also severe.

From The lay of the land in Binsted:

‘Binsted is a wonderful, mystical place, a little gem held in the past, vitally important in the life story of Laurie Lee. Here is an extraordinary example of a parish unblemished by the modern world, with an exquisite little Norman church whose timeless quietness and beauty must surely be left undisturbed in the 21st century.’

From A letter to Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden:

"The new dual carriageway will cross the Binsted Rife Valley on a viaduct a few yards from St Mary’s Church, Binsted, BN18 0LL, with traffic passing at the height of the top of the churchyard wall. St Mary’s must be the only 12th century church in the country to be built on the lip of a steep, secret valley created by melting ice at the end of the last Ice Age, and on top of an Iron Age earthwork.

"The earthwork under the church is part of the ‘War Dyke’ system around Arundel, linked to loops of the river Arun. Its massive banks run along the edge of the valley far into the South Downs. It divided the kingdom of Cogidubnus from an ‘Oppidum’ or enclave for trading with the Romans. The Grey route would sever the remains of the earthwork itself further south. ...

"In 1868 [the church] was restored by Thomas Graham Jackson, with a glass ‘Cosmati pavement’ in the chancel, like an Eastern carpet, in imitation of mediaeval work. The church is a place of pilgrimage, not just for its faithful congregation, but also for many who come here to enjoy its peace... The church has links to history going back 11,700 years to the end of the Ice Age, when the valley it overlooks was formed. The Iron Age earth bank system, War Dyke, is 2000 years old. The church itself is nearly 900 years old.

"This gem of history, prehistory and culture and would be devastated by the Grey route plan. The Grey route, 8km long, would ... cut through the ancient villages of Tortington and Binsted. It would destroy Binsted’s village life, such as its Strawberry Fair (which funds the upkeep of the church) and its Arts Festival. The death of Binsted village would be symbolised by the ruin of the precious cultural icon that is St Mary’s Church."

From Walberton Parish News, December 2020:

This Article explains the harm the Grey Route would cause to the 12th-century listed St Mary's church in Binsted, as it passes on a viaduct only 10metres from the churchyard wall; and the planning policy justification that would be required to allow such damage to irreplaceable cultural heritage.

The moral case

The Grey proposition is morally vitiated by democratic deficits, inadequate regard to people and wildlife both present and future, conflict with the imperatives of the climate and ecological emergency, conflict with cultural values. See for example the 15.10.2020 article by Tor Lawrence of Sussex Wildlife Trust, '£450 million to sever landscapes and principles'.

The political case

Political decisions need to keep pace with changing public awareness and perceptions, and the Department for Transport and Highways England, since they depend upon the public's money, should also take heed of this. The 2019 consultation, in which two thirds of respondents rejected all the big long bypass options for Arundel, suggests that politicians and Highways England have yet to catch up with changing public concerns.

There can be no place, if we are to tackle climate change adequately, for the type of silo thinking that promotes environmental achievement stories in one area, such as green business and technology, whilst leaving government bodies such as the Department for Transport and Highways England to continue facilitating increased carbon consumption both in road construction and in per capita travel. President-elect Joe Biden has, correctly, announced an "all-government" approach. Only such a consistent, integrated approach across all government departments can succeed. Should the climate emergency not be addressed in an adequately integrated way: it will become a key driver both of escalating inequality, and of political instability.

The practical case

There is a less damaging and less costly alternative

The practical fact is that whereas Highways England's case for the Grey Bypass is based on many unproven assumptions and false figures, there is a better more easily buildable and affordable solution, the Arundel Alternative, for an explanation of this concept see www.arundelalternative.org . It represents best practices for transport. In summary:

The Arundel Alternative, an uninterrupted, 40mph, wide single carriageway, between the Ford Road roundabout and Crossbush junction, would avoid current pinch points to improve traffic flow. Consistent with best practices in transport, there would be far less intrusion into the landscape, improved traffic flow, walking and cycling access across town and to the railway station, and improved safety. The Arundel Alternative also minimises new traffic and carbon emissions. It is the most likely solution to be affordable economically, and to be acceptable to the Planning Inspectorate because it is far less damaging.

Working from home is becoming the norm

Highways England's big bypass proposals, however beneficial to themselves as a road-building company, and to their construction industry partners, fail to take into account essential long term cultural changes which are already under way. As many of us have found, working from home is not only possible, it is productive. Technology accommodates this change, and will continue to develop in this direction as both companies and their employees discover the benefits, which were documented in Acas’s government funded research study “Home is where the work is: A new study of homeworking in Acas – and beyond” https://archive.acas.org.uk/media/3898/Home-is-where-the-work-is-A-new-study-of-homeworking-in-Acas--and-beyond/pdf/Home-is-where-the-work-is-a-new-study-of-homeworking-in-Acas_and-beyond.pdf.

Up-to-date research on homeworking in the time of pandemic is being undertaken by many, including Dr. Daniel Susskind, Fellow in Economics, Balliol College, Oxford University (https://www.wired.co.uk/article/covid-workplace-automation), and academics at Cardiff University and the University of Southampton (https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/news/view/2432442-uk-productivity-could-be-improved-by-a-permanent-shift-towards-remote-working,-research-shows), to name a few.

An investigation in the Financial Times on 2nd March 2021 wrote: “Companies are launching root-and-branch reviews of working practices, in moves that could have far-reaching consequences for UK city centres, after Boris Johnson outlined plans to fully reopen the economy by this summer. Some of the UK’s largest employers, including several in the City of London, have kicked-off projects that will determine when and how staff return to the office following the coronavirus pandemic. The Financial Times contacted more than 20 companies, and most said they anticipated introducing hybrid models of working in which staff split their time between the office and home.”

Road Pricing

From an article in the Guardian, 16.11.2020, "Road pricing could offset loss of fuel duty from electric cars":

“The government is exploring options for dealing with a £40bn black hole in the public finances, which would result from a proposed ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars within the decade…The chancellor, Rishi Sunak, is understood to be considering options for addressing the shortfall, with potential solutions including a new national system of road pricing – which would mean motorists paying directly to use Britain’s roads.”

Back in 2014, Peter Phillips of Highways England (in charge of the Arundel A27 Bypass project) said that within 10 years, they expected to see road pricing which would reduce and manage traffic and potentially make this kind of project redundant.

With homeworking becoming a norm that results in reduced in traffic, road pricing will be another reason people prefer to use their cars less.

If you would like support us, then send us an email with your contact details.

We will keep you in touch with Arundel A27 affairs by e-newsletter.